ꌗꉓꃅ꒒ꍟꀎ𝔻ꍟℜ𝕊𝕋𝕌ℝℤ

South African, living in Germany, left-leaning, deeply aligned with the opening lines of the Grundgesetz that declare all people to have inherent worth. Nerdy of nature and short of stature, I bend code and words to my purposes yet revel in my sports and thrive in the hills and high places.

- 4 Posts

- 13 Comments

1·2 months ago

1·2 months agoZed is very interesting. I know it.

Very recently, I found a fork of Zed that gutted the AI Assistant integration and Telemetry. I forked that, myself, and took it further: gutting automatic updates, paid feature-gating, downloading of executable binaries and runtimes like Node.js (for extensions that don’t compile to WASI), integration with their online services, voice-calling, screen sharing, etc.

My branch ended up down 140 000 lines[1] of code and up less than 300! It was educational and the outcome was absolutely brilliant, to be fair. In all honesty, forking it and engaging in this experiment took less than 24 hours even though I restarted three times, with different levels of “stringency” in my quest.

This experiment was very realisable. Forking Zed and hacking on it was quite possible – the same cannot be said for just “forking Electron” or “forking VS Code” or even getting up to speed on those projects to the point of being able to fix the underlying issues (like this OP) and submit merge-requests to those projects. They have a degree of inscrutability that I absolutely could overcome but would not, unless I was paid to at my usual rates. (I have two decades of professional development experience.)

I shelved the effort – for the time being – for a few reasons I don’t particularly want to extenuate, today, but I shall continue to follow Zed very closely and I truly, deeply hope that there is a future in which I see hope (and, thus, motivation) in maintaining a ready-to-go, batteries-included, AI-free, telemetry-free, cloud-free fork.

Part of maintaining a fork would include sending merge-requests upstream even though I should hardly expect that my fork would be viewed favourably by the Zed business. But, from what I can tell, Zed seem to act true to the open-source principles – unlike many other corporate owners of open-source projects – and I see no reason (yet) to believe they would play unfairly.

No word of a lie! The upstream repo is well over 20k commits and over 100 MB in volume. Zed is not a nice, small, simple code-base: it is VAST and a huge percentage of that is simply uninteresting to me. ↩︎

15·2 months ago

15·2 months agoI don’t see it as a “lol” matter.

The Electron project made an extremely stupid decision. Individual people who are left to wrangle with the fall-out and manage the PR have nothing but my utmost sympathy, as do all the down-stream projects (Signal, Discord, VSCodium…) who have to do the same. Even the developers of

xdg-desktop-portalare facing unnecessary backlash because of this. Their release schedule and time-line for whenorg.freedesktop.portal.FileChooserv. 4 could be reliably expected to exist in the wild was surely not kept in secret!

15·2 months ago

15·2 months agoThis doesn’t only affect Flatpak apps. The

xdg-desktop-portalmechanism is used by many things. Even “gtk native” applications like Firefox use it when running on a correctly configured KDE environment and one of the nuances of this issue is that those applications – today – continue to work perfectly. Electron is not part of their stack.I have

flatpakon my desktop just for Steam and even flatpak’d steam still seems to work, correctly.

21·2 months ago

21·2 months agoIt’s a good question for the package maintainers.

In their defence: it isn’t a direct dependency, it isn’t advertised, and it is likely that the distro package maintainers just don’t know about it – Electron hardly announce that they chose to depend on something that they know isn’t released, anywhere, yet, and won’t be for months.

25·2 months ago

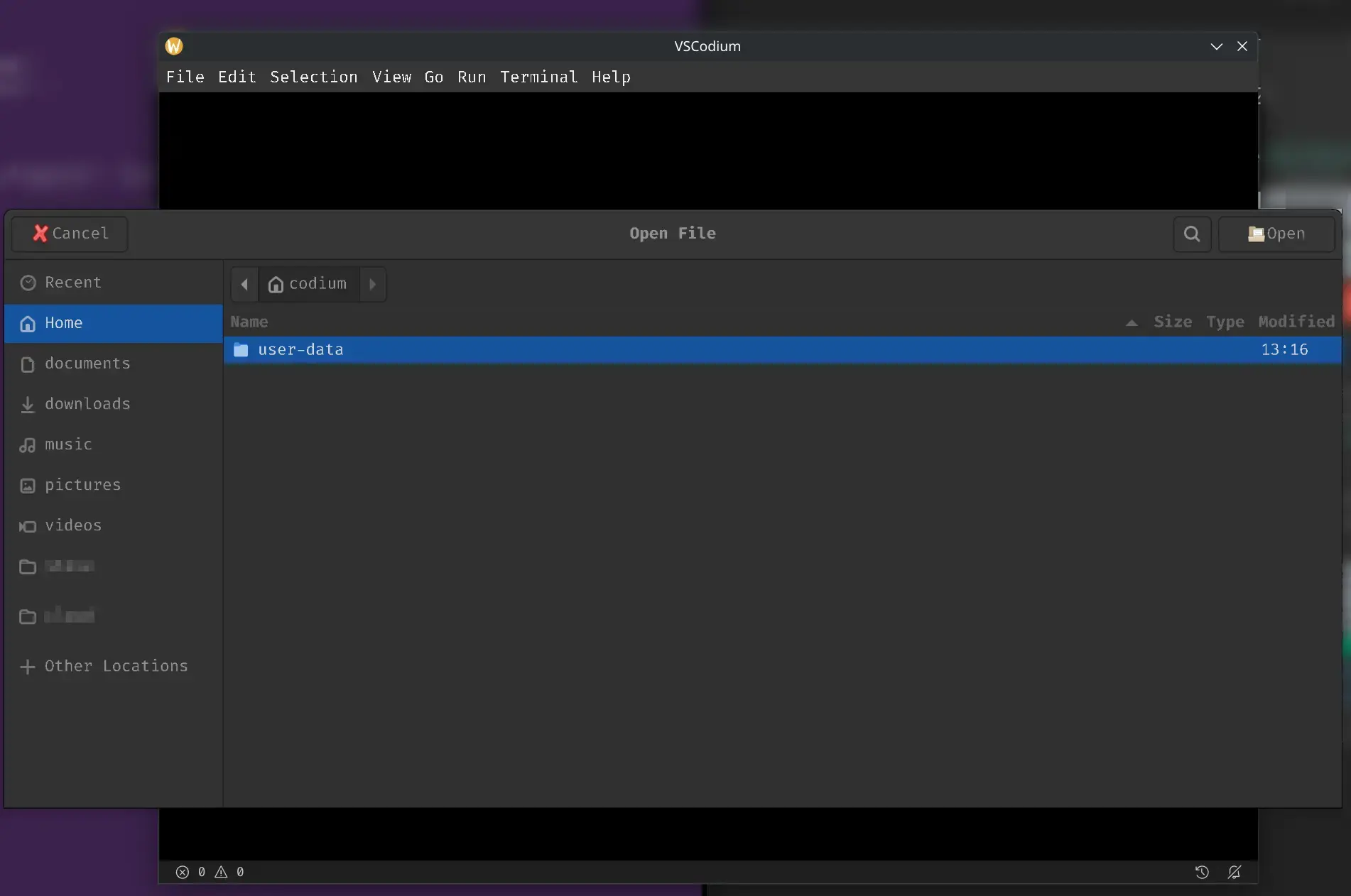

25·2 months agoTo lighten the mood, here’s a screenshot of one of the lowest points I achieved while hacking away, trying to resolve the issue:

What even is going on, there?

What even is going on, there?- pixelated menu

- “Cancel” button at the top left??

- “Open” button at the top right??

- clearly Adwaita but not actually Adwaita as configured – the VSCodium window (behind) shows how Adwaita is actually configured on my system and that’s how all native gtk applications actually draw.

1·2 months ago

1·2 months agoTaiga is too broad. I tried it out with all the best intentions and, quite simply, it is too big. It is too complex and complicated and feels extremely heavy to use.

From decades of professional experience, I know that all forms of planning are performed breadth-first and not depth-first. One jots down a bunch of titles or concepts and delves into them, fleshing them out and adding layers of detail afterwards. Taiga just doesn’t seem to facilitate that workflow.

It is focussed on fixed ideas like “epics” and “user-stories” and its workflow needs one to understand how your planning should fit into those boxes. I never work like that: I don’t know whether a line-item on a scrap of paper is an “epic” or a “story” or just destined to be an item in a bulleted list, somewhere within something else. I don’t want to have to choose what level of the plan the line-item fits before I capture it in my project tracker – I just want to type it up, somewhere, and be able to move it around or promote it or add stuff to it or whatever, later.

In summary: Taiga seems “fine” but just isn’t for me.

1·2 months ago

1·2 months agoI know Bugzilla from the days of yore. I haven’t actually used it since about 2007, I estimate, and I’m happy to say that your post didn’t trigger any hyper-ventilation or other post-traumatic-stress reactions so I do appear to be recovering. 🙃

You are right, though: it is very classic. And libre.

1·2 months ago

1·2 months agoI do like putting task-cards in columns and dragging them from left to right but I’m explicitly not going the Kanban route nor the Scrum route. I reject the prescriptivism that inevitably accompanies those “brand name” methodologies, even while I acknowledge that both methodologies do encompass several excellent ideas one might usefully borrow.

In fact, I always rather liked Trello simply because one could do whatever the heck one wanted with its boards – and the hotkeys were brilliant. (If I test out Planka, hotkeys will be evaluated for sure!)

Sadly, Trello devolved into and, yeah, I wouldn’t touch any Atlassian[1] product with a barge pole, today, nor have I in years.

Do they still charge for dark-mode in some of their products? Anyone who has managed a large team that includes neuro-diverse developers knows that dark-mode is tantamount to an accessibility feature and charging for it is just a dic•-move. ↩︎

1·2 months ago

1·2 months agoTa. Along with Taiga – which is presently first in the queue to try out[1] – I’ve added Planka simply because it looks so immensely and elegantly simple and down-to-earth. I shall not be surprised if Planka wins out from pure simplicity: that would be the same reason why I migrated my self-hosted environment to Gitea (from GitLab)

Planka actually looks to do precisely what I want where as Taiga appears to be an Eierlegende Wohlmilchsau. The latter is great when one actually wants wool, milk and pork, but I’m thinking I only want the eggs. ;)

Planka’s live demo is just so easy, too. And it does Markdown footnotes which Taiga doesn’t. I could live without them but… I LIKE FOOTNOTES. ↩︎

1·2 months ago

1·2 months agoI did know about the association with PenPot but hadn’t actually looked at that because that’s not what I’m seeking, presently. But, I did, now, and they are the same people and I also find it very reassuring to see this as No 1 in their FAQ, too:

Penpot is Open Source, and self-hosting Penpot will be free forever.

There are many recommendations in this thread – Wow! Thanks, Lemmy – but I think I shall begin with trialling Taiga, first, and report back on my findings.

1·2 months ago

1·2 months agoI’m fairly certain that the original authors recommended using another generator – like split-mix-64 – to extrapolate low-entropy seeds to the required state width. Using high-resolution time as a seed is common practice throughout software development and I think they were envisioning split-mix-64 to be adequate to get decent seed entropy from a linearly increasing timestamp. I’m certain it would be adequate to widen 32-bit seeds to the required width.

If my memory is correct, the reasoning was that split-mix-64 – although not as robust a PRNG as the XO*SHIRO family – is trivial to compute and reaches a reasonable level of entropy without needing many iterations.

It looks like[1] the state width is 256-bits, anyway – not 64 bits.

I’ve lost my references and don’t have time to go digging through archives right at the moment but I pulled up my Rust library that implements my PRNGs (which is a port of a C++ re-implementation that exploited learnings from implementing a C# library to replace Microsoft’s original, slow .NET PRNG, which was based on the research paper’s reference implementation, and ran in production for years and years…) ↩︎

1·2 months ago

1·2 months agoI’m thinking to try Taiga, next, but not today. Their pricing page doesn’t seem to indicate that self-hosted instances will be limited and there are other overtly positive signs on their site, too.

Self-hosting is an option they openly promote on the landing page. If you use

ctrl+fto search forself-host, you immediately find a link to documentation on how to do that.Has anyone any experience of Taiga? Horror stories? (Save me time!) Or good recommendations are also welcome.

There are many reasons.

Multiplayer games will only target Windows, officially, and might even ban Linux altogether because of the perception that anti-cheat is more costly, impossible, or just hard under Linux. True Kernel-level anti-cheat is not possible on Linux like it is on Windows but the real reason is risk: anti-cheat is an arms race between cheaters (and, critically, cheat vendors who would sell cheat tools to them) and developers and those developers want to limit the surface area they must cover and the vectors for new attacks.

The biggest engines, like Unreal, treat Linux as an after-thought and so developers who use those engines are not supported and have to undertake an overwhelming level of extra work to compensate or just target only Windows. When I was working on a UE5 project, recently, I was the only developer who even tried to work on Linux and we all concluded that Linux support was laughable if it worked at all. (To be fair to Tux the penguin: we also concluded that about 99.9% of UE5 was -if-it-worked-at-all and the other 50% was fancy illumination that nobody owned the hardware to run at 4k/60fps and frequently looked “janky” or a bit “off” in real-world scenarios. The other 50% was only of use to developers who could afford literal armies of riggers and modellers and effects people that we simply couldn’t hire and the final 66% was that pile of blueprints everyone refused to even look at because the guy who cobbled them together had left the team and nobody could make heads or tails of the tangle of blueprinty-flowcharty-state-diagramish lines. Even if the editor didn’t crash just opening them. Or just crash from pure spite.)

A very few studios, like Wube, actually have developers who live in Linux and it shows but they are very few and far between. (Factorio is one of the very nicest out-the-box, native Linux experiences one can have.) Even Wube acknowledge that their choice to embrace Linux cost them much effort. Recently, they wrote a technical post in their Friday Factorio Facts series about how certain desktop compositors were messing up their game’s performance. To me: this sort of thing is to be expected because games run in windows and render to a graphics surface that must be composited to some kind of visible rectangle that ends up on screen: after a game submits a buffer to be presented, nearly all of what happens next is outside of the games control and down to the platform to implement properly. Similarly, platform-specific code is unavoidable whenever one needs to do file I/O, input I/O, networking or any number of other, very common things that games need to do within the frame’s time budget – i.e. exceedingly quickly.

Projects which are natively developed on Linux benefit from great cross-compilation options to target Windows. This is even more true with the WSL and LLVM: you can build and link from nearly the same toolchain under nearly the same operating system and produce a PE .exe file right there on the host’s NTFS file-system. The turn-around time is minimal so testing is smooth. For a small or indie project or a new project, this is GREAT but this doesn’t apply to many older or bigger projects with legacy build tooling and certainly does not apply as soon as a big engine is involved. (Top tip: the WSL will happily run an extracted Docker image as if it was a WSL distribution so you can actually use your C/I container for this if you know how.)

Conversely, cross-compiling from Windows to Linux is a joke. I have never worked on a project that ever does this. Any project that chooses to support Linux ports their build to Linux (sometimes maintain two build mechanisms) if they weren’t building on Linux for C/I or testing, already, anyway. (Note: my knowledge of available Windows tooling is rather out of date – I haven’t worked with a team based on Windows for several years.)

Godot supports Linux very nicely in my experience but Godot is still relatively new. I expect that we might see more native Linux support given Godot’s increase in population.

What’s that? Unity? I am so very sorry for your loss …

If you’re not using a big engine, you have so many problems to handle and all of them come down to this: which library do you choose to link? Sound: Alsa, PulseAudio or Pipewire: even though Pipewire is newer and better, you’ll probably link PulseAudio because it will happily play to a Pipewire audio server. Input: do you just trust windows messages or do you want to get closer to some kind of raw-input mechanism? Oh: and your game window, itself? Who’s setting that up for you, pumping your events and messages and polling for draw? If your window appears on a Wayland desktop, you cannot know its size or position. If it’s on X11 or Win32, you can. I hope you’ve coded around these discrepancies!

More libraries: GLFW works. The SDL works. SDL 3 is lovely. In the Rust world, winit is grand. wgpu.rs is fantastic. How much expertise, knowledge and time do you have to delve into all these options and choose one? How many “story points” can you invest to ensure that you don’t let a dependency become too critical and retain options to change your choice and opt for a different library if you hit a wall? (Embracing a library is easy. Keeping your architecture from making that into a blood pact is not.)

NONE of this is hard. NONE of this is sub-optimal once you’ve wrapped it up tight. It is all just a massive explosion of surface-area. It costs time and money and testing effort and design prowess and who’s going to pay for that?

Who’s going to pay for it when you could just pick up a Big Engine and get the added bonus of that engine’s name on your slide-deck?

And, then, you’re right back in the problem zone with the engine: how close to “first-class” is its Linux support because, once you’re on Big Engine, you do not want to be trying to wrangle all of these aspects, yourself, within somebody else’s engine.