PointAndClique [they/them]

roindroundroud

- 8 Posts

- 22 Comments

9·9 months ago

9·9 months agoFirst I’ve heard of it and am subbing now.

9·10 months ago

9·10 months agoDefinitely a useful distinction.

20·10 months ago

20·10 months agoTrue and interesting to note. OOP says ‘dawn of humanity’ though, not recorded history, so taking 200k as ‘human history’ is also valid.

41·10 months ago

41·10 months agoFugu and a Orion tinnie sounds about right

5·10 months ago

5·10 months agofwiw Adam Liaw has Malaysian-Chinese heritage not Japanese

6·11 months ago

6·11 months agoYes sorry about that, I had the same link as you but accidentally cut off the https:// of the URL which apparently made it go belly up. Thanks for re-upping.

Likewise, I reckon Keating is no slouch, he was bang on with his comments re AUKUS earlier this year, and current Labor are doing themselves a disservice for not heeding his warnings imo.

5·11 months ago

5·11 months agoOP shared the letter in the body text:

https://www.malcolmturnbull.com.au/media/statement-by-former-prime-ministers-of-australia

7·11 months ago

7·11 months agoMr Keating yesterday published a statement saying he would not sign onto the letter “drafted by” The Zionist Federation of Australia.

Anyone got a link to Keating’s statement?

Edit: found it

5·11 months ago

5·11 months agoI think you have all the elements you need to switch your attitude towards games, so first off, well done on having the awareness to identify the issue and to begin asking how to go about remedying it.

Let’s talk about competitive games first and the attitude towards winning and losing

Recognise that you’re not going to win every game. You may even lose some games that looked like a sure bet, and you may win some games that looked like a certain loss. This is the inherent fun in many competitive games - the outcome is uncertain. If you stop trying and self sabotage, the outcome will always be certain, i.e. it will always be a loss.

If you recognise this, then every game is worth playing through to the end, and if your opponent is also decent, as most players are, they will recognise your efforts for trying your hardest.

You can also put the shoe on the other foot. Imagine that you’re playing a really close game and after battling hard, things have swung in your favour. You want to keep fighting through to the end to secure the victory. Imagine now that the opponent at this moment throws in the towel, and torpedoes the game. This hollows out your victory. Don’t be that player. Try to empathise with your opponent as someone who equally deserves a chance to enjoy the game and compete for a worthy victory.

Finally, learning how to turn a loss into a win is a skill in and of itself. Executing a comeback is sometimes more satisfying than a complete stomp, and more entertaining for all players of the game. You won’t practice that if you check out as soon as the tide is against you, and you’re depriving yourself of some more fun games.

Now let’s look at an attitude to improving your overall skill

Some people take the attitude of looking at their long term skill as a player, and this may include their rank, win/loss ratio or season stats. Since they take a macro view, one loss may not detract from their long term improvement and helps put their temporary upset at losing into perspective. Even if you lose games on average, you can set yourself a target to strive for. The losses will still suck, but if you self sabotage then you also scuttle your long term goals.

Part of this may be an approach of wanting to improve focussed skills within the game that don’t rely on win or loss, per se, but will help build your overall proficiency. This may be perfecting your early game setup and speed, or your ability to execute on a particular strategy, or to lay traps for your opponent. Since I don’t know what games you play I can’t suggest what that would look like, I’ve just used general terms. You need iterations to work out what’s effective, and a loss is useful information that a strategy, when followed through, may not be effective. If you don’t learn from that then you may repeat the same mistakes, leading to more losses in the future.

You may also take this as an opportunity to recognise shared mechanics across games, so that playing a game is a chance to improve at others, too. Does this game have a similar economy to other games you’ve played, or hand management, or push your luck elements.

Now let’s look at an attitude of enjoying the game for its own sake

If you and your opponent are giving it your all, then sometimes the whole aspect of win/loss can dissolve away, and be replaced with sheer enjoyment of trying your hardest regardless of the outcome. Trying to wrack your brain when you’re behind and wring out every possible mechanic or avenue for victory can be just as exhilarating as trying to hold onto a seemingly unassailable win. Trying to find that flow state where you don’t care about the outcome is worthwhile, I hope you can seek it out.

Finally, don’t mourn your defeat, instead, celebrate your opponent’s victory

You tried every trick in the book, and they still won. Wow, that’s impressive! After the initial sting of loss, congratulate your opponent and turn their victory into your own. Compliment their strategy! Ask them how they managed to pull off that trick on the third turn. Ask if they have any tips, or how they spotted the gaps in your plans. If they’re a gracious winner, they will be happy to talk shop when the round is over. If you share in their win, you make up in some way for your loss, rather than doubling down on those negative feelings.

This goes especially for boardgames or games where you know the other players and opponents. If they’re your friends or family, then you should be happy that they’re happy and they’ll in kind work to assuage your upset in defeat rather than letting you sulk.

I realised this because I play a lot of boardgames with a good friend, and as soon as the scores are tallied, the first thing we always do is congratulate one another for a good game and immediately turn to talking about how one another played and what we’re going to try next game. It turns even a competitive game into a team effort where we’re working together to eke as much enjoyment out of the game as possible, and push one another to try harder next round.

So yeah, share the joy don’t dwell on the woe, and you’ll turn every win into something to be celebrated together.

I won’t talk to playing cooperative games, as other posters have addressed that. Putting yourself as a me/them into an ‘us’ game can divert your pastime to something more productive, but it may not break down your ‘sore loser’ problem enough that it wouldn’t be an issue when you return to competitive games.

If you want a good video, I like Otzdarva’s explanation of how not to get ‘tilted’ in online games.

1·11 months ago

1·11 months agodeleted by creator

75·11 months ago

75·11 months agomaybe big emoji

Good on you

Good on you

3·11 months ago

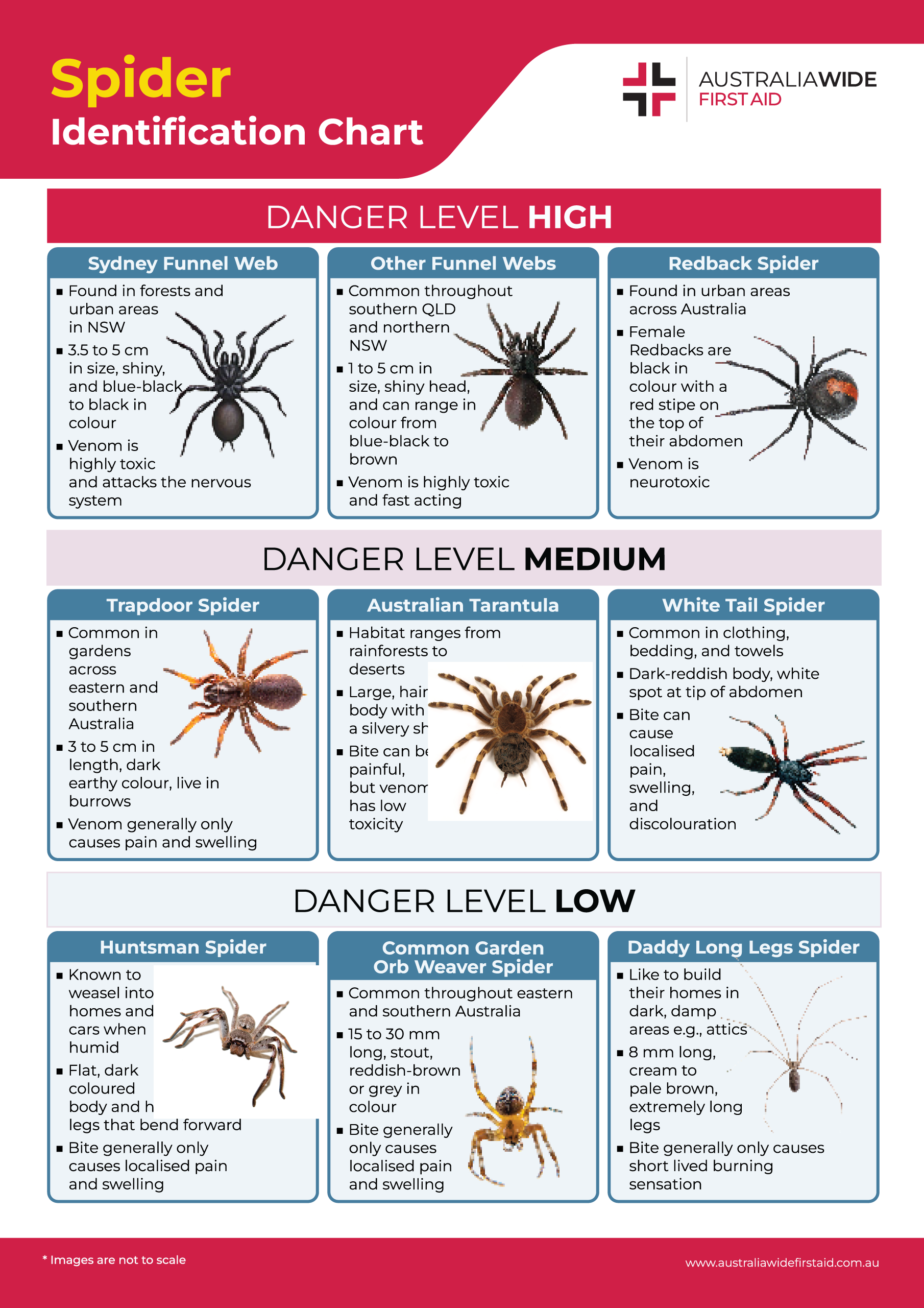

3·11 months agoSorry for replying to my own comment, this kinda feels like a bit of a puzzle. It could also be a juvenile huntsman which also seem to have that lighter colouring. In which case they’re your pal! Huntmans (huntsmen?) are great spiders, I love having them around the house to keep other pests down.

4·11 months ago

4·11 months agoI can’t ID it. I was thinking maybe it’s a juvenile Orb Weaver, due to its thin, long front limbs, lighter colouration and relatively small thorax. The little spinerrets (two tooth like tail bits) are throwing me though because the Weavers don’t seem to have them like that?

In any case as Instigate mentioned below, it doesn’t appear to be anything super harmful. Here’s a quick guide:

242·11 months ago

242·11 months agoThere’s a user in this thread calling us the genocide deniers while Israel unceasingly and unrepentantly destroys Gaza and its people. Like. No self awareness. No historical awareness. Just ‘Oh I have a more nuanced view of the situation’. Nuance my fucking gooch.

191·11 months ago

191·11 months agoWe’re active in political threads since we’re both explicitly leftist instances (grad is ML, Hexbear is leftist of different stripes). Hexbear doesn’t have down votes so if we see something we disagree with, we say something. There’s not really a ‘downvote and move on’ mentality, so you’re likely to get multiple users replying to a post.

261·11 months ago

261·11 months agoLol I browse All, I see a thread with lots of comments, I drop in. Nobody’s looking for you, get over yourself. Take the L. Sit out your 30 days and ply your debate pervert shit somewhere else in the meantime, the Internet is a huge place.

19·11 months ago

19·11 months agoNeoliberal economists boast about this with supply chain abstraction through I, Pencil, a work by Leonard Read then adopted by Milton Friedman.

Search ‘Nobody knows how to make a pencil’ and you’ll get thousands more hits than searching for commodity fetishism, Friedman basically repackaged Marx and sold it as a positive of free market economics.

They basically took commodity fetishism and fetishised it.

8·11 months ago

8·11 months agoFetishisation and fetishism are similar, but not quite the same, as I understand it.

Fetishisation is related more to the overvaluation and/or sexualisation of something.

Fetishism is the process of making something a ‘fetish’*, or the embodied form of abstract ideas which then supplants or discards the ideas it came to represent.

(*Similar to an ‘idol’ in the process of Idolatry)

I think I’ve got that right someone please step in if not. In common usage I think the two terms are basically interchangeable (let’s say that searching either term online is almost NSFW) however in this case they are not.

12·11 months ago

12·11 months agoI found Wallace Shawn’s explanation of Commodity Fetishism to be very enlightening.

Resharing below under the spoiler tag

"About a year ago I spent a day at a nude beach with a group of people I didn’t know that well. Lying out there, naked, in the sun, there was a man who kept talking about “the ruling class,” “the elite,” “the rich.” All day long, “The rich are pigs, they are all pigs, some day those pigs will get what they deserve,” and things like that. He was a thin man with a large mustache, unhealthy-looking but very handsome, a chain-smoker. As he talked, he would laugh—sort of bitter barks that came out always unexpectedly. I’d heard about these words and these phrases all my life, but I’d never met anyone who actually used them. I thought it was quite entertaining. But for about a month afterward a strange thing happened. Everywhere I went I started getting into conversations with people I met—on a train, on a bus, at parties, in the line for a movie—and everyone I met was talking like him: The rich are pigs, their day will come, they’re all pigs, and on and on. I started to think that maybe I was crazy. I thought I was insane. Could this really be happening? Was everyone now a Communist but me?

"And this was all happening at the very same time that Communism had finally died, and social pathologists were arguing over what had caused its death. The newspapers and magazines reported no nostalgia for the defunct system, and it seemed as if all the intellectuals and political leaders who had ever been known to have fallen under its sway were running in all directions looking for shelter. So then who were all these people who kept grabbing hold of me?

"One day there was an anonymous present sitting on my doorstep—Volume One of Capital by Karl Marx, in a brown paper bag. A joke? Serious? And who had sent it? I never found out. Late that night, naked in bed, I leafed through it. The beginning was impenetrable, I couldn’t understand it, but when I came to the part about the lives of the workers—the coal miners, the child laborers—I could feel myself suddenly breathing more slowly. How angry he was. Page after page. Then I turned back to an earlier section, and I came to a phrase that I’d heard before, a strange, upsetting, sort of ugly phrase: this was the section on “commodity fetishism,” “the fetishism of commodities.” I wanted to understand that weird-sounding phrase, but I could tell that, to understand it, your whole life would probably have to change.

"His explanation was very elusive. He used the example that people say, “Twenty yards of linen are worth two pounds.” People say that about every thing that it has a certain value. This is worth that. This coat, this sweater, this cup of coffee: each thing worth some quantity of money, or some number of other things—one coat, worth three sweaters, or so much money—as if that coat, suddenly appearing on the earth, contained somewhere inside itself an amount of value, like an inner soul, as if the coat were a fetish, a physical object that contains a living spirit. But what really determines the value of a coat? The coat’s price comes from its history, the history of all the people involved in making it and selling it and all the particular relationships they had. And if we buy the coat, we, too, form relationships with all those people, and yet we hide those relationships from our own awareness by pretending we live in a world where coats have no history but just fall down from heaven with prices marked inside. “I like this coat,” we say, “It’s not expensive,” as if that were a fact about the coat and not the end of a story about all the people who made it and sold it, “I like the pictures in this magazine.”

"A naked woman leans over a fence. A man buys a magazine and stares at her picture. The destinies of these two are linked. The man has paid the woman to take off her clothes, to lean over the fence. The photograph contains its history—the moment the woman unbuttoned her shirt, how she felt, what the photographer said. The price of the magazine is a code that describes the relationships between all these people—the woman, the man, the publisher, the photographer—who commanded, who obeyed. The cup of coffee contains the history of the peasants who picked the beans, how some of them fainted in the heat of the sun, some were beaten, some were kicked.

“For two days I could see the fetishism of commodities everywhere around me. It was a strange feeling. Then on the third day I lost it, it was gone, I couldn’t see it anymore.”

Reject tikataalik who left the water to walk alone on land, accept tiddalik who sucked up the water so all had to walk